This LSAT Diary is from Nicholas in Wyoming. He has some great insight into what it'll take for him to rock the exam, and his background's pretty interesting, too.

Nicholas' LSAT Diary:

Greetings all from sunny Wyoming, which prides itself on being a such a frontier western state that there's a bumper sticker, "Wyoming, not for everybody." Seriously, I saw it the other day!

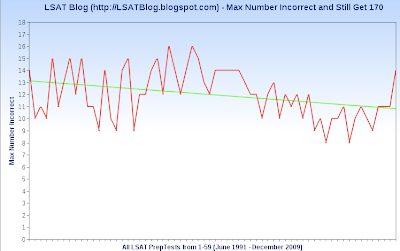

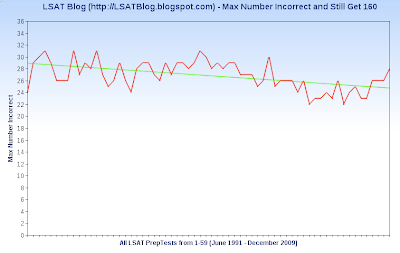

I'm 29 years-old, just out of college, working full time at a blue-collar warehouse job here in Laramie WY, married with three children, an army vet having served 4 years active duty, and now dedicated to getting a law degree. I'm a law school hopeful looking to attend the University of Wyoming law school in the fall of 2011. The reason I call myself a law school long shot is because my GPA isn't the greatest, and in order to have a 50 to 75 percent chance at getting into the school I'm looking at (University of Wyoming) my LSAT score must be at least 165. Not the greatest odds, but I'm sure i can do better than my old high school buddy who took the test last year and got a 138. So I'm looking at a June or October test date.

My aspirations may be a bit lofty, but I'm only trying for one school, here at the University of Wyoming, and if I don't succeed it's no skin off my teeth because I have other back up plans. I'm saving the good personal stuff for my personal statement, so for right now I'll talk about my interest in the LSAT, my situation as far as scheduling is concerned, my study goals, my study plan, and my thoughts on the test in general.

For the next year, I have dedicated myself to learning all I can about the LSAT, which I must admit is both driving me crazy and intriguing me all at the same time. Crazy in the fact I feel like an idiot after completing a practice logic game without fully reading the rules or creating a ridiculously complicated diagram. We'll visit that later when we get to my study strategy. Intriguing because logic is so crucial to understanding the test, given time and effort, it can be tamed and used to my advantage. A phrase I often tell myself is, "what one man can do, another can do", and so I have decided to take the plunge and attempt to conquer the LSAT.

First off, tip of my hat to Steve for providing a wonderful study resource, which I admit I have been reading obsessively lately. Armed with Steve's advice, I am following his

four month LSAT study regimen. Combining that with my schedule requires a bit more time management than I'm used to, so we can begin there. I'm 29 years old, an army vet having served 4 years of active duty in the US Army as a paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne Div. and a year stint in S. Korea from 1999 to 2003. I came back to Wyoming and enrolled at the only four year university in the state, aptly named the University of Wyoming, in 2004 and graduated in 2009. If you do the math, I spent more time in college than I did in the military, but that's another story entirely.

I received my bachelor's degree in journalism and with the state of the media right now, I'm currently employed at a grocery warehouse 40 miles away where I make double and sometimes triple the hourly wage of your average entry level reporter. I don't mind that people value food more than journalism, but given the fact that my job could be done by monkeys driving forklifts, it's a bit disconcerting knowing my degree is collecting dust while I freeze my ass off in the refrigerated receiving dock unloading crates of processed cheese and bologna. I am married with three children, all under the age of 7, and am the primary breadwinner because my wife is enrolled in nursing school. So in the meantime I spend my week, Tuesday through Friday, taking care of the kids, doing chores, and cooking dinners while my wife is away at school. On the weekends (Saturday through Monday) I drive the long commute to the warehouse, where I work an 11 hour swing shift that starts early in the afternoon and ends very early in the morning.

Now that we have that out of the way, let's talk about my LSAT strengths and weaknesses. I'm a funny case, I'm a nerd for logical thinking, but have a hard time doing it myself. So in terms of the test, my only strength is the reading comprehension and the writing portion of the test...at least in terms of clarity and conciseness, which I have practice with due to my journalism background. My big weakness is logical thinking, but I'm a skeptical reporter, so hopefully that's my way into cracking this test. My degree in journalism has made me a more empowered skeptic, but I need to sharpen my logic if I plan on accomplishing what I set out to do: score a 165 or better.

I started my study regimen two weeks ago, completing

Steve's list of basic linear games from preptests 19 - 38. My study habits are improving, I've just started the LSAT study regimen and have kept to it...somewhat. Like I said, I have three kids and my wife is in school so it leaves me with just enough time to cover what I need.

According to the study plan, I was supposed to add advanced linear games to the plan, but my performance in basic linear was pretty bad, so I extended it another week. I squeezed in the testpreps whenever I could: While the kids were taking their naps, during down times when I'm waiting to pick up my son from school, early in the morning while everyone is asleep, late at night while everyone is asleep, and during the small breaks at work.

Doing the preptests exercises at work is more tough, because of the limited time and because every Tom, Dick, and Harry come by my table in the breakroom and ask about what I'm doing. They either ask me what I'm studying for, and go blank when I tell them it's the LSAT. Others ask me about the particular question I'm working on, and when I respond they give me another blank response. So basically I'm pestered every five minutes by guys who are intrigued and bewildered by the nerdy kid burying his nose in a book. I get less grief from my kids for pete's sake!

So it took me a good week to work out all the logic game problems and about a couple of days to redo the ones I did terribly on. From my assessment, I have concluded I can think logically, but struggle in a few key areas: Attention to detail, making key deductions for more complex games, and focusing on one scenario so much I lose track of other possibilities.

It's a different way of thinking, and like I said before, both frustrating and fascinating at the same time. It's too bad my study regimen can't be done through some Hollywood montage. How much easier it would be for the

Rocky theme to be playing while shots of me working out problems, getting frustrated at first, doing situps with huge rocks, finding that eureka moment, growing a beard, smoking through timed tests, and that moment where I climb the snowy summit and yell out "LSAT!" whiz by the screen and afterwards I arrive at the testing center and ace it.

But life doesn't work out that way and I'm left to work things out the slow and steady way. I'm halfway through week 2, and am finding it very challenging but rewarding because the LSAT isn't some math theorem that hasn't been solved for centuries, it's only a standardized test with only one right answer for each question. With that in mind, and the fact that there are guys out there who have scored in the 99th percentile, it's possible.

A friend of mine in the army told me about his sports heroes, and how they weren't always the most naturally gifted athletes on the field. In fact, he said, they were better in his eyes because they had to work twice as hard to get to where they're at. I suppose he saw a bit of himself in those guys, or maybe a piece of himself that felt it was possible. I feel the same way about the LSAT. I'm not the most gifted test-taker, but with enough practice and determination, anything is possible right?

Thanks for your time and more to come when I get to advanced linear games.

Photo by afagen

Rosemary's first LSAT Diary gave some tips on getting started with LSAT studying. In her second LSAT Diary, Rosemary dealt with the distraction of watching TV, found a study space, and visited her first-choice law school.

Rosemary's first LSAT Diary gave some tips on getting started with LSAT studying. In her second LSAT Diary, Rosemary dealt with the distraction of watching TV, found a study space, and visited her first-choice law school.