.

Don't look at these explanations until you've taken PrepTest 61 as a full-length timed exam.

Also see:

PrepTest 61 (October 2010 LSAT), Game 1 ExplanationPrepTest 61 (October 2010 LSAT), Game 2 ExplanationPrepTest 61 (October 2010 LSAT), Game 3 ExplanationExplanations for Recent LSAT Logic Games***

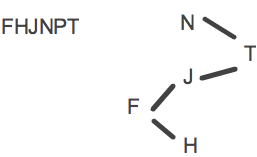

This game concerns seven nurses: Farnham, Griseldi, Heany, Juarez, Khan, Lightfoot, and Moreau who are placed in order, 1st through 7th.

Here's a very basic initial main diagram:

Explanation of basic initial main diagram:

Explanation of basic initial main diagram:I wrote down "H/M - ? - ? - M/H" because there are at least 2 nurses between H and M, but there could be more. I've kept things open-ended by representing this with dashes, rather than as a block. I put down H/M and M/H because we don't know which one comes first. The question-marks signify the nurses coming between H and M.

I put down GK with a box around it to indicate that they must be consecutive in that particular order. J later than M is represented with "M-J" meaning that since M is to the left of the dash, it's occurring earlier than J, which is to the right of the dash.

F before K but after L gives us the general ordering of "L - F - K". However, since there is a GK block, the ordering becomes "L - F - GK" (with a box around the GK).

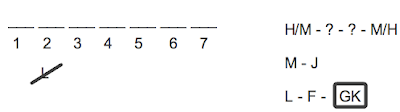

Since L can't go on 2, place an L with a slash through it under the 2nd space.

***

Now, L can't go on 2, and we know that it can't go too late because it has at least 3 variables (F, G, and K) occurring after it. This makes me think about where L might go.

It seems like L could only go on 1, 3, or 4.

However, if we place L on 4, a problem arises:

L on 4 forces FGK to go on 5, 6, and 7, respectively.

We can then try to space apart M and H. Since M must go before J, we can put M on 1 and H on 3. However, we need at least two spaces before M and H. As such, L on 4 is impossible. This leaves L to go on either 1 or 3.

If L's on 3, we can't have the GK block on 4-5, since we need to have F between them. Therefore, when L's on 3, we can either have the GK block on 5-6 or 6-7.

When L's on 3 and the GK block's on 5-6, F must go on 4. When L's on 3 and the GK block's on 6-7, F could be on either 4 or 5.

This gives us the following two possibilities:

Now, keeping in mind the other rules:

-M and H have at least two nurses between them.

-M is before J.

We know that in the top possibility I've drawn, one of M or H must go on 7 in order to keep M and H spaced relatively far apart. We can't have M on 7 because then J would have no room to go after it. Therefore, in that diagram, H must go 7th, M must go 1st, and J must go 2nd.

In the bottom possibility I've drawn, one of M or H must go on either 4 or 5 (depending upon which one of those F goes on) in order to keep M and H spaced relatively far apart. M can't be the one to go on either 4 or 5, because then F would go on the other one of 4 or 5, and we'd then have no space to place J after it. Therefore, in that diagram, H must go wherever F does not. In order to keep M before J, M goes on 1, and J goes on 2.

We now have:

These represent all possibilities for when L is on 3. However, we still have the more open-ended possibility where L is on 1.

In this scenario, F before the GK block must occur somewhere in the remaining spaces, H and M must have at least two nurses between them, and M must go before J. M/H on 2 or 3 seems fine, but having either M or H on 4 is problematic. If H was on 4, we'd need to have M on 7, but then J wouldn't be able to fit after it.

On the other hand, if M was on 4, and H was on 7, we wouldn't be able to fit GK after F while still fitting M before J.

If the GK block is on 5-6, J can't fit after F. If the GK block is on 2-3, F can't fit before it. Therefore neither M nor H can go on 4 when L is 1st.

Here's everything we have so far:

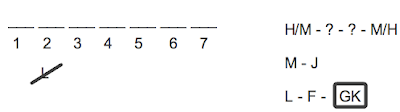

Now, we can split apart the diagram with L on 1 based upon the placement of the GK block. We know GK can't go on 2-3 because we need F before it. It seems that GK can go on 3-4, 4-5, 5-6, or 6-7.

However, placing GK on 3-4 creates a problem. How can M and H have at least 2 nurses between them when they can only go on 5, 6, or 7? It won't work. As such, GK can only go on 4-5, 5-6, or 6-7. (I've numbered the possibilities on the left side for quick reference.)

In Possibility 3, M and H must be split across 2 and 5 in order to have at least two nurses between them. Now, we know that M must go before J. As such, M will go on 2, H will go on 5, and F and J will be interchangeable on 3 and 4.

In Possibility 2, one of M and H must go on 7. It can't be M because M has to go before J. Therefore, H has to go on 7. Within spaces 2, 3, and 4, we must fit M before J, and then F's floating around within any of those 3 spaces. As such, there are only 3 possibilities for those 3 slots based upon the various placements of F (shown in below diagram).

In Possibility 1, F must go on either 2 or 3 in order to go before the GK block, and J must go on either 6 or 7. If J was on 3, we'd need to have M on 2, and then we wouldn't be able to fit F before the GK block.

This all brings us to our...

Final Main Diagram:

Every valid scenario falls within one of these possibilities.

For those of you who are still reading, it's time to *

finally* move on to the questions. First, a comment/caveat:

I know people are going to ask me whether making all these initial inferences is really necessary. The answer is a firm "No." You can get all the questions right without doing all this work beforehand, but doing this will make the questions go more smoothly.

The method you choose depends upon your level of comfort with spending more time in the initial setup, as well as your ability to diagram quickly.

Even if you don't have the time to make all of these inferences and still have the time to get to the questions, that's ok. Again, you don't have to make all these inferences, but I still want to get you thinking about the fact that it's possible to make them. While they might give you more information than you need for these questions, it's better to have too much information than too little.

It's now time to (finally) move on to the questions themselves.

Question 18:Since our diagrams contain all valid possibilities, we can simply eliminate those answer choices that don't fit the scenarios we've already drawn.

Choice A can't happen in any of our possibilities. Eliminated.

Choice B can't happen in any of our possibilities. Eliminated.

Choice C can't happen in any of our possibilities. Eliminated.

Choice D is identical to Possibility 2B. It's our answer.

Choice E can't happen in any of our possibilities. Eliminated.

Of course, you can also solve this question simply by taking the basic rules one at a time and applying them to the choices.

Using that method:

Choice E has only one space between H and M, not the required minimum of 2. Eliminated.

Choice C has J before M, not M before J. Eliminated.

Choice A has F before L, not L before F. Eliminated.

Choice B has L on 2. Eliminated.

Question 19:Where can't J go? Scanning vertically through each of our possibilities, J's never gone on 5. Of course, J's never on 1 either, but 1's not a choice. (Making 1 the answer instead of 5 would be a little too easy, given that we know it off-the-bat from the simple rule that M is before J). Choice C's our answer.

Question 20:If J's 3rd, we must be within Possibility 2C or Possibility 3.

If an answer choice doesn't happen in either of those two possibilities, we know it can't be true.

Choice D, G on 5, occurs within Possibility 2C, but none of the other choices occur in either possibility, so they're eliminated.

Question 21:If K's before M, we must be within Possibility 1, because all of the others have M before K.

In order to have K before M in Possibility 1, we must have M on 6 and J on 7. This would then require F and H to be interchangeable on 2 and 3. F is not a choice, but H is, so choice B's our answer.

Question 22:If G's on 5, we must be in either Possibility 2 or 4. The correct answer has to occur in both possibilities in order to be a "must". Choice B, H on 7, occurs in both, so it's our "must". I'll run through the others anyway.

Choice A occurs in 2B, but not in 2A, 2C, or 4. Eliminated.

Choice C occurs in 2A and 2B, but not in 2C or 4. Eliminated.

Choice D occurs in 2, but not in 4. Eliminated.

Choice E occurs in 2B and 2C, but not in 2A or 4. Eliminated.

Question 23:We know L could be on either 1 or 3, but those are the only possibilities, so Choice A is our answer.

Choice B, L on 4, is probably the most tempting wrong answer for those who didn't make the initial inference that L couldn't be on 4, but we've got it under control.

Photo by gbaku Hope everyone celebrating Thanksgiving had a happy one!

Hope everyone celebrating Thanksgiving had a happy one!